Hypercomf is a multidisciplinary conceptual design artist identity, founded by by artists Ioannis Koliopoulos and Paola Palavidi. Established as a fictitious company profile in Athens in 2017, it has since set out to explore the relationship between nature and culture, domestication, industry, and science. Hypercomf’s practice fosters interdisciplinary collaborations and community engagement methods of production often including a range of biodiverse participants. These processes are manifested as space activations, multimedia artworks and sustainable design prototypes and objects, structured around dynamic narratives that feature both organic and inorganic protagonists.

Tell us a few things about your background and how you decided to start Hypercomf in 2017.

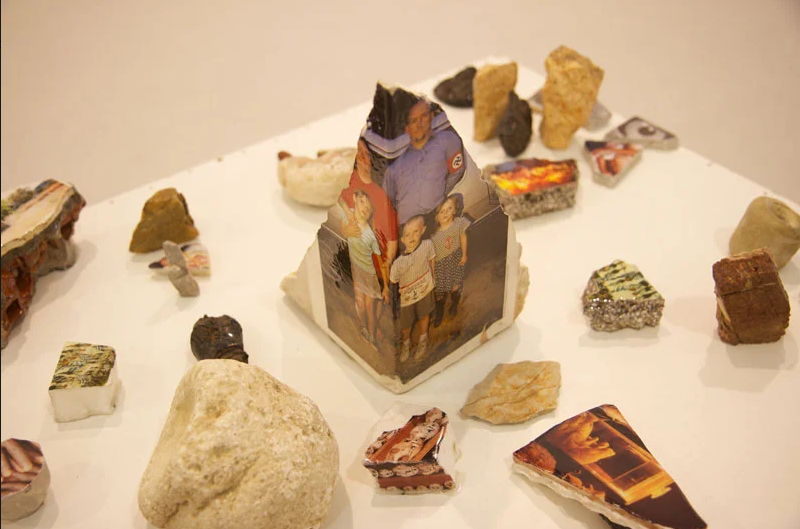

Hypercomf Team: We are two artists who have been collaborating very closely for more than ten years, in 2015 we exhibited a series of jointly produced sculptures and large collages for the first time publicly in Athens.

In 2017 we decided to jointly create the artist identity “Hypercomf” for two main reasons. Firstly, we wanted to divert the focus from our names and ourselves more towards the work. We personally didn’t connect with the importance that is given on the name of the artist, their personality, mental authority, or character, and we wanted to create a more abstract and fluid entity that we also believed would be a more welcoming situation for collaborators from varied backgrounds. Secondly, as we had been witnessing the global rise of self-branding, we were curiously drawn to this dramaturgy, mostly taking place online, and wanted to experiment with an avatar, a fake brand, so Hypercomf presents itself as a fictitious company.

The name is a word mash-up, Hyper and comfortable, in the custom of industries adopting “exotic” and futuristic sounding names.

How did you come up with the idea of “Peanut Pod and Film Seed Festival”?

H.T. We moved to Tinos island in 2011, to live in Komi village – one of the communities surrounding the Leivadi area, where Film Seed Festival took place.

We have been cultivating family owned land in Leivadi since then, in small scale, to provide for our home and we also practice beekeeping on a more professional level (our thyme honey comes from a coastal area close to Leivadi and it was used to make the hyper-local peanut “pasteli” treats offered at the festival)

As years went by, we became attached to Leivadi, a labyrinth of reed tunnels and small farmlands, and the stories of the generations of farmers who have been continuously cultivating its fields for hundreds of years to provide for the surrounding villages. At the same time, it was very obvious, and people continuously pointed out that the farmer profession was dying out.

For decades people have been leaving the countryside looking for better work opportunities in the city, in addition, a rapidly growing seasonal economy created by the tourism industry has been slowly absorbing all the remaining residents.

Many efforts are being made to keep the agriculture sector in Tinos alive, but it is clear that much more needs to be done and realistically, some motivation needs to be directed towards building year-round resilience.

When we encountered the Smart Agriculture challenge of the S.T.+ARTS Repairing the Present program, it presented a very interesting opportunity, to examine if an artistic methodology that brings together multidisciplinary collaborators could begin to address some of the struggles that make the farming profession a difficult career choice for the younger generation. Things we considered were the laboriousness of the actual farming practice, the difficulty in independently reducing costs or adding value to the final product, and socially and culturally, a strongly felt sense of being isolated, forgotten, and left outside of the social structure and culture that you sustain. These are common issues of small farming communities around the world.

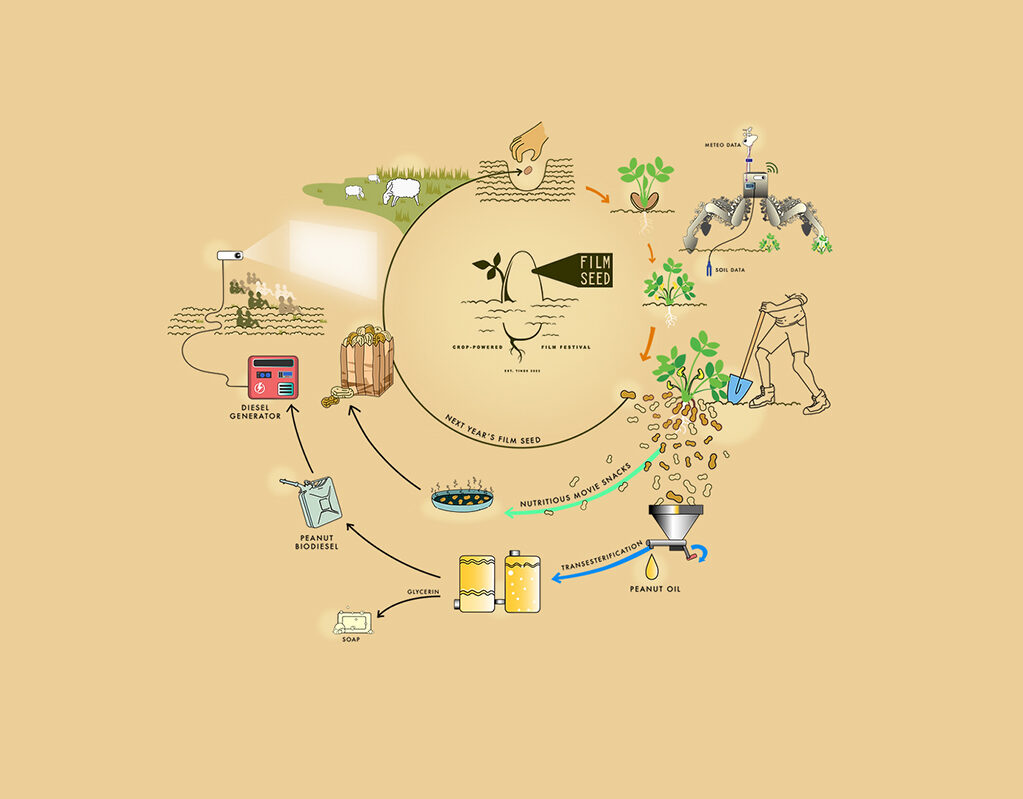

So, the first Film Seed Festival was cultivated as a harvest ritual in modern terms. A crop of peanuts was cultivated in a 1000sqm field using the aid of smart agriculture technology to reduce water use, cost, and effort.

The resulting crop was used to cover the energy needs of the festival, we needed electricity for the three nights and nutrition in the form of snacks for about 300-400 visitors. The festival was set up in the very same field it was cultivated, inviting the consumer to experience culture in the same place where his food is grown. To access the festival field people had to walk along a farm road and reed tunnels that passed through the neighboring fields of potatoes and artichokes.

At the end of every night of film projections, when it was pitch black in the middle of Leivadi, they had been advised to have flashlights(which every mobile phone has) which they used to walk back to the main asphalt road. through the natural pitch-black darkness. In the end it illustrates one idea, one of many possible scenarios where people collaborate to reclaim their cultural, nutritional, and energy independence. Hopefully, it motivates people to consider and design processes that best serve their individual communities’ needs.

The way that it works combines traditional techniques and modern technology. What would the benefits be if this method was widely applied in agriculture?

H.T. In technology there is a global uniformity of function that attempts to resolve common issues that humanity faces, whereas tradition usually has a much more localized and specialized function that addresses a specific need of a specific community.

We think it is important to consider both functionalities when planning real-life applications for a planet as culturally and geographically diverse as our own.

Traditional techniques currently sustain billions of people. To expect small communities where technological development is still at a very basic stage to suddenly implement the technological efficiency of large-scale agriculture is unrealistic for multiple reasons. But small-scale, targeted technological applications can definitely assist and complement the traditional techniques people currently use.

For example, in our case, in Leivadi, the land has been divided among families for hundreds of years. A farmer usually has many small fields he cultivates, in separate locations, each field’s location probably has a slightly different microclimate, soil type and vegetation. Although farmers in time develop a very good skill and ability to process all these parameters in their head, ultimately the only way to be sure if you need to water your crop is to physically drive to each field in order to observe if the crop needs watering.

By placing smart sensors in each field , he could assess the need for watering from home, save a lot of time and fuel, and avoid underwatering or overwatering his crop which can bring about weeds and diseases that then need chemical intervention.

There is also a misconception that tradition is by definition “old” and technology is “new”, when clearly there exist new traditions and old technologies. Perhaps there are cases where developing a new tradition can have equally empowering effects as developing a new technology. Hopefully Film Seed festival is the beginning of a new tradition with such empowering effects.

How are you planning to confront the challenges faced by farmers in adopting IoT in the agricultural sector? (connection issues, high cost of equipment, maintenance, data encryption)

H.T. We are artists by profession, so addressing the technical or infrastructural challenges of implementing these technologies is not our aim, specialty, or intention.

Where artists can contribute is in finding innovative ways to implement these technologies within cultural frameworks.

One of the mentioned issues that we can efficiently address with our professional skills though, and actually in novel ways that perhaps only multidisciplinary creativity can, is the issue of tackling the high cost of adopting these new technologies.

Many farmers we spoke to, say they can actually produce good quality and quantity produce with minimal technology. The major problem as they say is not producing the food but making a decent living from selling it. It is hard to discuss the possibility of technological development when you are barely making enough profit from your harvest to fund next year’s crop planting. How do you add value to your products so that you can invest back in developing and maintaining the helpful technology you need for your farm or for your community in general?

This is why all steps lead to setting up the festival.

The festival process is hopefully a useful and motivational example of how you can identify new and unexpected value in your product. Thoughtfully develop and then efficiently represent the narrative of who you are, and how you produce, to be able to add value to your hard work. People eat with their mouth but also with their mind as food time has always been story time.

During Film Seed Festival we gave out the peanut snacks for free and didn’t charge a ticket for the film projections and that is what will happen in all future versions, but in a different scenario, things like that could serve as additional income for farmers.

It also helps to create such occasions simply because they serve as fertile breeding grounds for more direct consumer to farmer relationships.

“Peanut Pod and Film Seed Festival” brings together people from different backgrounds and job sectors. How important do you think this co-existence is nowadays?

H.T. It is immensely important, our belief in this importance is the reason we mostly create artworks in the form of narrative procedures that are executed by bringing in collaborating people from different backgrounds.

The processes of Film Seed Festival involved multiple farmers from the region, technology providers, environmental engineers, local cooks, sound technicians, seamstresses, local community unions and of course, the wonderful creators and directors of the documentaries featured in the festival’s program.

It’s very easy nowadays to end up in a situation where you are constantly surrounded by your like, soothed by the confirmation they provide to your opinions, and then to wake up suddenly and realize, that what you thought was an organically build “tight” social group, is in fact a “target group” created by some intricate marketing strategy.

Being isolated in this way means you create a very strong attachment to your group’s ideas and rules, so they seem to be the golden solution to everything . A society that openly communicates, whose judgment doesn’t stem from a simple, soothing habit of inflexible mentality, and a society that is aware of all aspects of its composition, is a healthy society that takes the best-informed decisions.

You have already been part of a rural Tinos community for another project of yours. Could you share some of your experiences and their impact? What were the first reactions or feedback you received from the local farmers? How did you engage them in the project?

H.T. Last winter we presented the project Resonate, which was a two-year research on the traditions of song and textile production on Tinos island, two traditions with fragile archives, and with barely any surviving documentation dating back more than a few decades. Resonate’s goal was to collect everything we could find that was in some way documenting the past of these practices, generate a public ally accessible digital archive of our finds and experiment with ways we could use art and technology to motivate a revival of these practices. The digital archive can be accessed online directly or by visiting our website.

In order to motivate this aforementioned revival, we collaborated with the women of the Zarifeios Technical School for women in Tinos in producing new embroidered textiles on the school’s traditional wooden looms.

Their embroidered patterns were completely newly generated symbols, inspired by Tinian culture and meteorology, their patterns on the textiles represented average yearly windspeeds on Tinos island.

These textiles combine to form a long tapestry which became the base for an interactive multimedia sound installation created in collaboration with composer Stylianos Dimou. This was installed last December at the women’s school in the loom workshop with the help of digital composer Konstantinos Baras. Sounds of wind recorded on the island and songs from the archive were uploaded to a digital software by Dimou which could then be accessed and sound mixed in real time by any person standing in front of the tapestry, simply by him moving his hand in front of it, like a maestro of an invisible orchestra, a digital camera was tracking his gestures in the room.

So, people on the island already know us as artists, and they know that we plant our fields, and we keep chickens and bees so in a sense we didn’t do something really surprising. Of course, they find it curious how we combined art and agriculture, and a bit confusing how art can be something so other than a painting, a video or a crafty object, but that is not specific to farmers, most people we encounter outside the art world find it a bit confusing too. We try to explain in some way that art is just any conscious effort at harnessing the poetic potential of materials and gestures.

You have taken over quite some successful projects. Do you think there is one of them a “milestone” for you? And why?

H.T. The milestone was actually when we moved from Athens to the countryside.

Most of our recent work comes from experiencing life on an island which can provide a unique perspective on things.

On an island, everything is magnified, and every problem that modern society faces are even more complicated to deal with. Energy is a problem, all our energy and fuel come from Athens by boats and cables, the recent placement of wind turbines on the island has infuriated the residents, food independency is a problem, most of the consumer goods come by boats from elsewhere, all the previously mentioned things are obviously more expensive for island residents with the added costs of transport. Pollution and waste management is a problem, there is no treatment facility for waste on Tinos, the sanitation services collect them, pack them up in huge white plastic sacs, and stack them one on top of the other in a place called Vourni out of sight for the more than million tourists that help fill them in the summer. Οceanic pollution is a problem. Water scarcity is a problem, the tap water is not drinkable in most places, some years it rains and more often it seems lately, some years it barely does, and the effects of climate change are felt more intensely. In the city, it is easy to forget where things come from, as they seem to just be magically coming out from the concrete walls, like the water that Moses conjures from the rock.

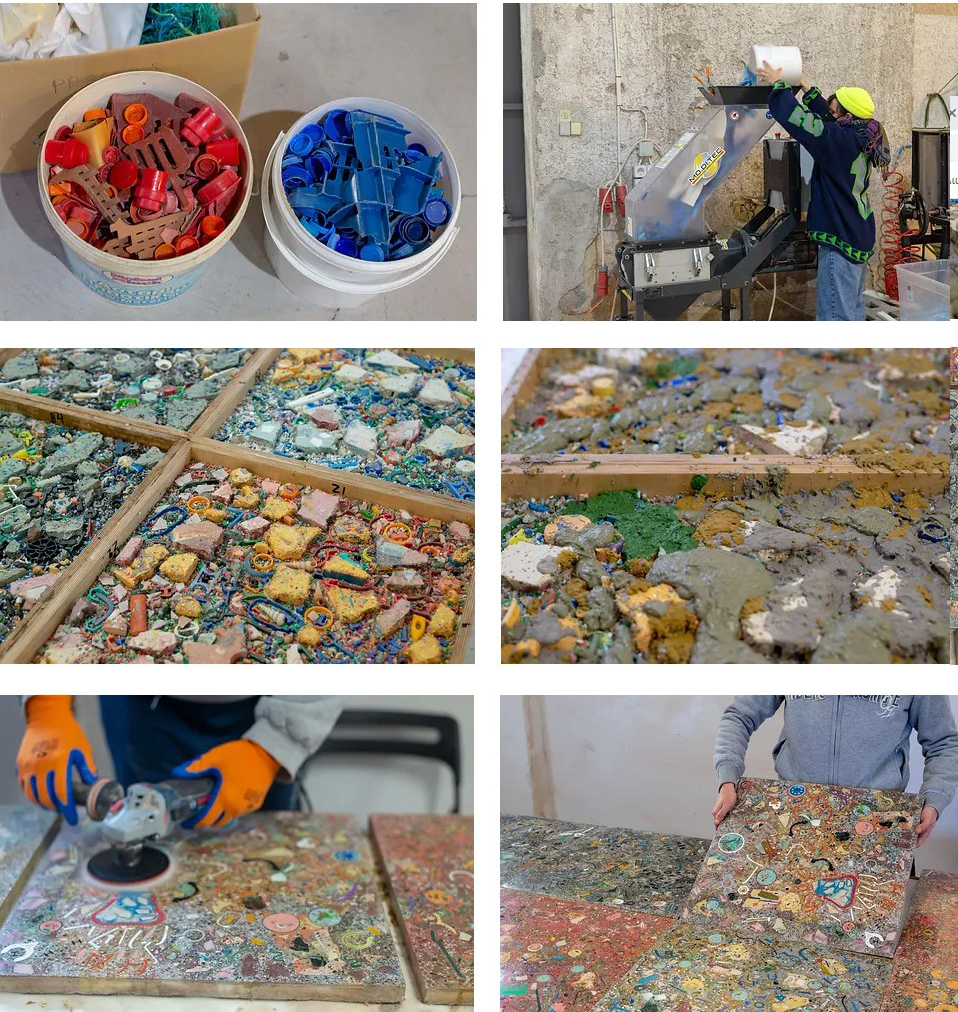

So, Film Seed Festival comes from thinking about food independency, and energy independency, from thinking how will small aging communities stand their ground in front of the powerful mass tourism industry, Benthic Terrazzo, the sustainable floor tile prototypes we are developing come from thinking what to do with all this trash we were collecting as it is washed ashore everyday along with dead marine life.

It can’t be recycled, and what’s the point in putting it in the trash it will just end up in a plastic bag in Vourni, where the goats will tear it apart and re-release the trash in the sea which is less than one kilometer away from this open dumping ground.

Biosentinel, the large transportable solar cooker project again examines, food, energy, and community, the incredible difference between the level of technological advancement of different places on the planet, in one place people don’t have drinking water and in another, they are launching giant rockets in space, sometimes for no urgent reason, Anthemis looks at citizen-built biodiversity archives, it is a work in progress in collaboration with Archipelago Network in Syros.

Even when we headed out from Tinos to live in New York for a 6 month as resident artists at Pioneer Works Culture Center our research application idea came from living on Tinos island.

Our starting point was the -originally Italian- tradition of building dovecotes and pigeon keeping which is very characteristic of Tinos, then we found out that the same tradition-again carried on by Italian refugees- was alive but fading out in Brooklyn, New York. There the “Brooklyn flyers” are an intricate community of rooftop pigeon keepers who even “compete” with other rooftop keepers by show-flying their flocks which by the way they absolutely adore. So, we decided to start a research into urban biodiversity and its interaction with humans, and in specific the bird population and the first step was making contact with different Brooklyn Flyers, using this common connection with Tinos pigeon keeping as an entry point for discussion. We had with us a lot of post cards of the beautiful Tinos Dovecotes which we handed out to the people we met. By the end of the 6 months we had collected an archive of video footage which linked the narratives of Brooklyn rooftop pigeon keepers, a scientist who hunted down feral pigeons in the streets of New York with a net gun to study their DNA, and a group of “freegans”, people who similarly to every other non-human organism of the urban ecosystem, live off the incredible amount of food waste generated by this megacity. This footage was edited to create the experimental documentary “Polycelium.net” presented in Greece at the recent Athens Biennale.

Film Seed Festival was developed as part of S+T+ARTS Residencies commissioned by Onassis Stegi and in collaboration with AGENSO and ACT4ENERGY – Democritus University of Thrace Spin-off.

READ ALSO: Giulio Vesprini's new artwork "E SOM DAL GATTO - Struttura G069" in Reggio Emilia, Italy