The dissertation aims to examine the process of dwelling through the study of body dressing. Throughout the analysis, garments are considered as shells that are inhabited by the human body in an attempt to enrich our understanding of space habitation. Considering both the garment and the house as cultural constructions charged with significations, the analysis follows a cyclic trajectory, based on the assumption that these meanings are “shaped” together with the construction of the shell, to be later on transmitted to various recipients and are finally experienced by the dwellers, redefining habitation and reseeding the construction process. This cyclic course is accurately described in the word HABIT which expresses both the meaning of dress and habitation. It also expresses the idea of practice, a repeated action which is the basis for rethinking and redefining dwelling.

1_home is where I take my clothes off

Although we usually tend to understand garments as objects that we hold, carry, store, care and generally treat and use, garments, when unfolded, have the specificity to create geometries inside which the human body enters. A garment can be an object as well as an environment and therefore our body has to find a way to accommodate inside it. Garments are shells which create spaces; Small-scaled, soft portable houses which we carry every day on our bodies when we appear in the social world and take off when we return home.

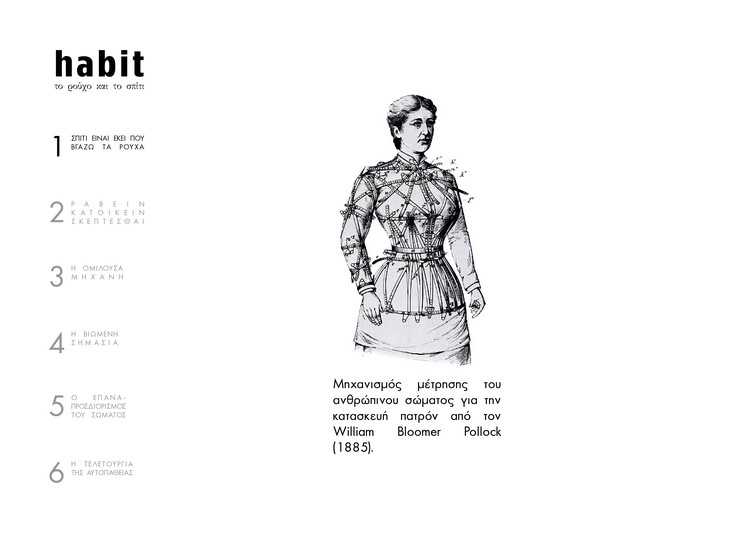

Clothes retrieve their morphology from the boundaries of the human body as they inscribe its geometric characteristics on the textile. This dialectic has also an inverse course. Garments can also shape the human body which now becomes the object of elaboration. They can function as tools which help us explore our physical boundaries or even shape them. Although it appears to be a strictly personal object, destined for the individual body, a garment can also produce spatial relations between various persons, influencing the way they interact. Understanding garments as shelters we bear in public space, it is obvious that these control our social interactions through the human gaze, which implies a level of control. Dress determines the quantity and content of information we give about ourselves in public, functioning as a device through which we regulate this data.

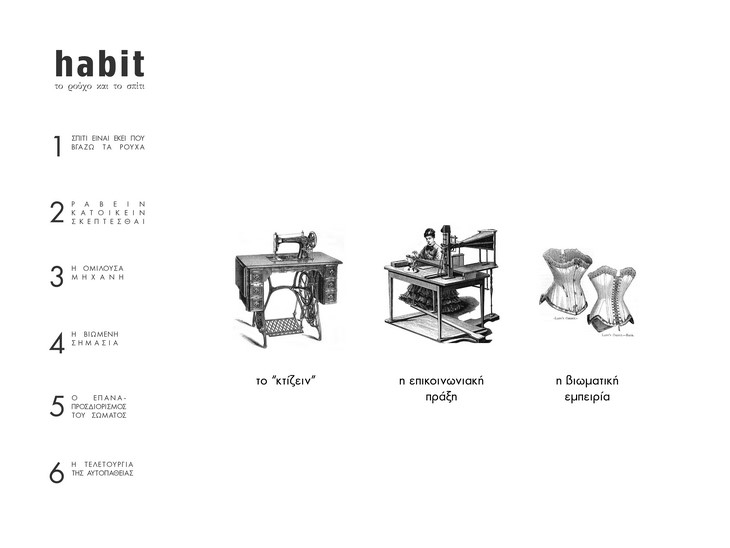

2_dwelling – sewing – thinking

Human beings conceive, construct and shape various habitable shells. During this morphing process, a primal matter is utilized and its inner order is changed according to specific criteria. At the same time, pretensions originating from previously experienced spaces are projected on the designed object or space, while statements of desirable ways of living are made. The architect or craftsman working on the creation of a shell reflects on the way it will be inhabited and this reflection is expressed on the applied art. While working on an object the craftsman learns about the properties of materials and the methods for their elaboration. He learns to work with matter and therefore he builds wider categories of “good” as Sennett defines them.

Lastly, the fabrication process is carried out through a procedure of “constructing” significations and in the case of garments it is mostly the expression of an effort to form an identity which will be later exposed in public, initializing a communicational interaction. It is therefore obvious that during the construction of a habitable shell, its semiotic function is simultaneously structured. The “intelligent hand” of the craftsman constructs meanings.

3_the speaking machine

The information sent out through our garments is based on semiotic codes and signification systems formed inside human communities. Garments render the human body a moving emitter which propagates data concerning the characteristics of the person that inhabits them.

In order for the sign of this semiotic function to be interpreted it is necessary that the applied dress-codes are addressed to an audience that is able to read them and therefore decode them, an audience trained to the specific cultural conventions. An individual belonging to a human community comes across a series of established semiotic conventions which are necessary in order to communicate elements for a basic recognition of his/her identity. At the same time, the individual learns to interpret these conventions forming part of this trained audience.

Therefore dress can be described as a language, which we “speak” addressing it to other subjects. It is a system of relations which codifies and permits to decode several messages. A constructum, as Bourdieu describes it, to which the individual act of speaking abides. In the case of dress this constructum is fashion, from which a person retrieves the codes to “speak” about him/herself and give clear information to the others so that they can place him/her into the various social hierarchies.

The use of dress as a communicational instrument sets the receiver of the emitted messages to the position of an observer who evaluates the data he receives. The human behaviour thus depends very much on the expectation of this evaluation which leads to the conclusion that the human gaze has a power of control upon us, based on the anticipation of social judgment.

This consideration of the garment as a communicational instrument can also be applied to the built environment and more specifically to the houses we inhabit. The way in which we organize and dwell our house is also a process of constructing identity, just like the clothes we choose to wear. The interior of the house and the objects it contains, as well as the way that these are ordered are a kind of garment with which we “appear” in public.

Although we tend to understand habitation as a private condition, in reality all of the social structures are present even in the most private territory of our home, where through the so-called domestic order a kind of social conformity takes place.

4_the experienced signification

Habitation is also an experiential procedure during which a person experiences the social world, while the habitable shell returns to us the properties that we assigned to it during the “building” process. The human body becomes the receiver of the shaping forces which origin from the shell’s physical and semiotic characteristics.

At the same time, the human body activates all of the social structures that have been previously inscribed to the shell. Non-material social and cultural forces effect on the body through social demands and the result of this procedure is purely visible and material.

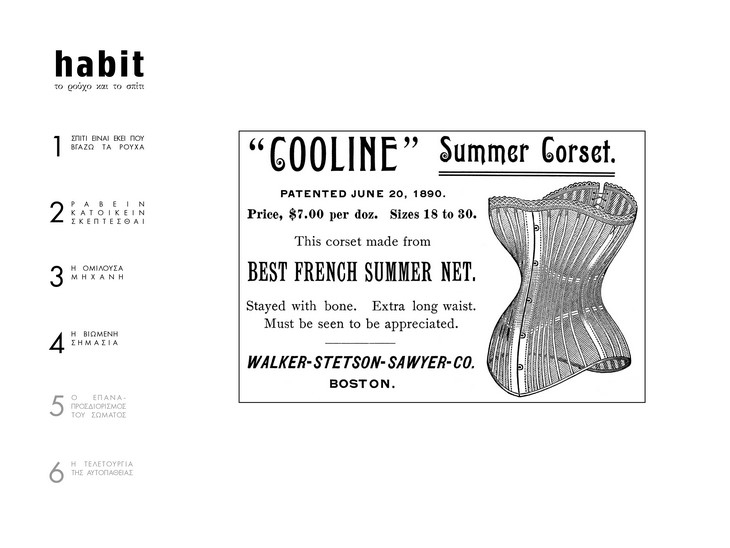

An indicative example of this shaping process is the corset, which has been used during the 19th century to express the person’s abstinence from any physical, productive activity. The corset is used to literally make the body look less vital and capable of physical labor.

Especially during the Victorian era women used it to narrow down their waist, deforming their bodies and influencing even the order of the internal organs. Women had to learn how to breathe inside the corset as it pressed their lungs to extreme levels. However, further examination shows how in some cases the physical, corporeal experience has led to the emergence of different significations than the ones imposed by social conventions, resulting a contrast between the established semiotic function of the garment and the subjective perception.

According to historian David Kunzle, although during the Victorian era the corset was related to morality and prestige, many women used it with a totally different meaning, based on the corporeal experience of it. Various testimonials show that those women practiced its tight-lacing in an act of concealing pregnancy or even aborting. This was, according to Kunzle a protest against women’s repression from the imposed maternity and at the same time a painful expression of women’s sexuality.

This story brings forward the importance of the “speaking subject” as Umberto Eco defines it, which is capable of altering the signification systems. According to Boudieu this is possible through practice, which enables us to appropriate social structures and redefine them. Bourdieu describes this act as an orchestration without conductor, as it is impulsive and does not derive from a spoken accordance. Therefore, habitation is a bidirectional mutation process, in which the habitant can appear both as the subject and as the object of various alterations.

5_the redefinition of the body

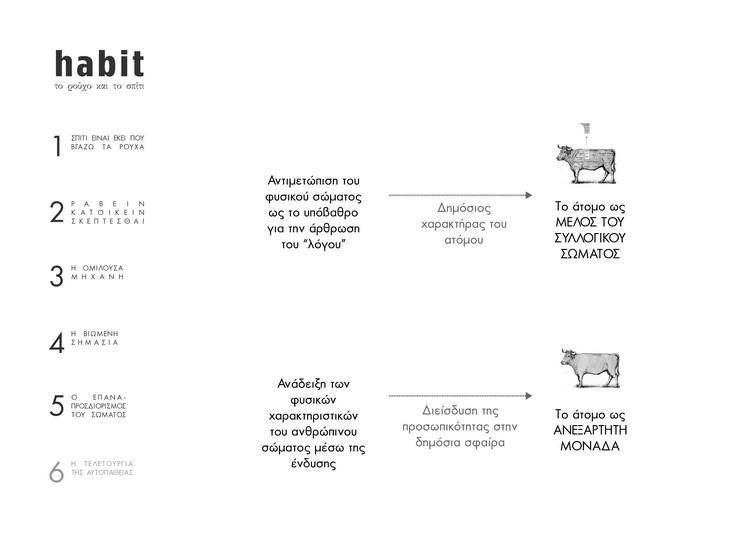

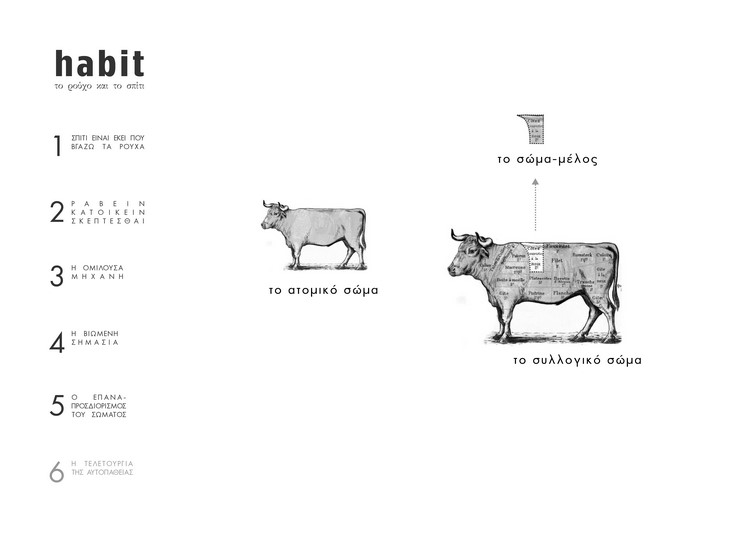

This analysis leads to the conclusion that the interaction between individual and collective, between private and public, is the ground on which the cultural dimension of the body is formed.

On that basis, it would be useful to define in each case the subject of habitation, as the various spaces that we dwell are not inhabited by individual persons. We can always spot traces of collective habitation processes even in the most individual shells, such as the garment, if we think on the power of social judgment and the necessity for social approval.

Two types of bodies that inhabit shells can be defined, the individual body and the collective body, which would be an aggregation of bodies-members interacting with each other, creating a collective identity and behaviour as a result of interdependence and orchestration.

Inside the house the body occupying the shell is the collective body of the habitants who cooperate under the condition of physical coexistence. Interaction here stems from the necessity to cohabitate a common space. Furthermore, in the built domestic environment, fields of different levels of privacy are formed within a spatial territory. Individual privacy and collective life occupy distinct zones at different degrees. At the same time, the fields of interaction are also fields in which the habitants expose their identity in public, as they open their house to “strangers”.

The public condition is also present inside the domestic reality, determining the way in which the space will be inhabited under the weight of social judgment. This condition results the individual’s behaviour inside the house to be coordinated with behaviours of other individuals in different houses. Specific semiotic contents are the ground for this coordination, which attenuates in the most private zones and intensifies in the common areas.

In this case, the cultural content of habitation forms collective bodies, although there is no condition of physical co-existence. These bodies are now orchestrated under intangible forces by sharing a common cultural construction. In the case of women who practiced excessive tight-lacing, a new collective body emerged within an already existing social group. This was formed by the impulsive coordination of individuals who experienced the corset in the same way and found in it specific significations. These had not been assigned to the garment before and could not be explicitly expressed in the specific social and cultural context.

On that basis, the most important changes in the history of European fashion practically reflect our understanding of individuality and social interaction. The degree to which the physical characteristics of the human figure are highlighted through garments in every period is the physical imprint of the way that the individual person is understood either as an autonomous unit or as a member of wider organisms.

6_the reflexive ritual

As Richard Sennett explains while analyzing the work of a craftsman, the experience obtained through fabricating material things can be converted into an instrument for “shaping” human relations, because the abilities we have as social beings are derived from our own body.

Recalling Sennett’s logic of considering the search of categories of good as an applied art, the habitant of a shell can also be considered as a craftsman who intents to find and achieve “good” modes of habitation. The habitant elaborates his/her own body and identity using the habitable shells as instruments.

Habitation is therefore a cultural ability that can be gained. We learn to inhabit a garment or a house and this practice is the ground on which we obtain abilities related to our social substance. The material avocation of constructing shells is not very distant from the cultural process of “building” and elaborating an identity using these shells as tools. When we shape a garment we know that it will return to us the properties that we assigned to it. The garment and the house will shape us. This process calls for a physical condition in order to happen and this physical-material condition is the craftsman’s instrument.

National Technical University of Athens, School of Architecture

January 2014

Supervisor: Panayiotis Tournikiotis

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU  HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU  HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU  HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU  HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU  HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU  HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU

HABIT: THE CLOTHE AND THE HOUSE / RESEARCH THESIS / DAFNI PAPADOPOULOU READ ALSO: CHRIS LO / EXODUS REVERSION / INFRASTRUCTURE FOR DISOBEDIENT AUTONOMY